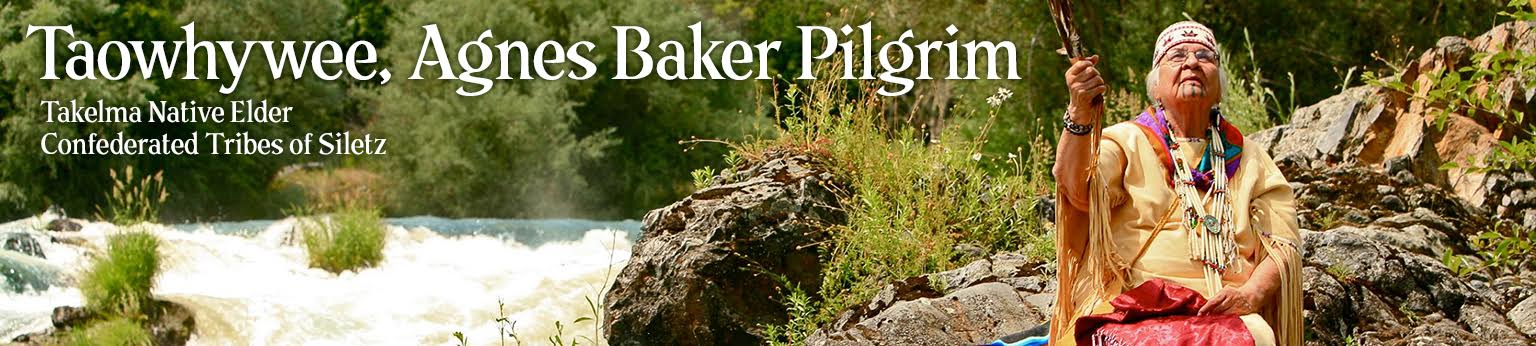

Agnes’ Ancestors

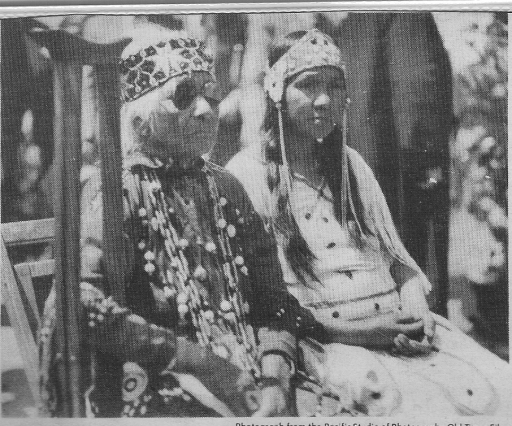

Great Aunt Frances Harney Johnson and Mother, Eveline Harney Baker

Agnes Pilgrim’s ancestors (Takelmans, speaking a Penutian language) included beloved tribal leaders who were very active in their traditional villages along the Rogue River. After being defeated and forcibly removed to the new Siletz and Grand Ronde Reservations in 1856, survivors in Aggie’s family continued to serve with great dedication.

In 2013, Oregon Public Broadcasting produced the video, “River of the Rogues” (28 min.), with Aggie describing how her ancestors lived along the Rogue River for thousands of years (estimated at 13,000 to 15,000 years ago, when the Ice Age melting began).

Her Great-Great Grandfather “Tolt-nys,” or Jack Harney, was a chief born in the 1700s, with five sons who also became leaders: Lympe, Tyee George, Bill, Jim, and Jack.

Aggie’s Great-Grandfather, Jack, or “Shulth-tah-sah” (Song in mid-air), lived from 1815-1895. Aggie’s Great-Grandmother, Taowhywee (translated as Morningstar) or Margaret, lived from 1807-1893 and was a respected Takelma medicine person. They had three children, Frances, Agnes, and George (Aggie’s grandfather). Their home territory was up Jump-Off Joe Creek north of Grants Pass.

Great Uncle Lympe was a chief, and his name was given to a creek flowing into the Rogue River near Finley Bend, an ancient tribal fishing camp near Grants Pass. Lympe was one of the signers of the 1853 Rogue River Treaty, but he did not relocate to the reservation at Table Rock north of Medford. During the attacks by settlers in the fall of 1855, Chief Lympe sought to avoid trouble by moving further down the Rogue River to the confluence with the Illinois River near Agness.

By 1856, the attacks and counter-attacks throughout the Rogue Valley had greatly escalated, and many Native American survivors were fleeing downriver into what is now the Wild Rogue Wilderness. On May 20, 1856 Chief Lympe and upriver chiefs Cholcultah and Tecumtum (Chief John) met with Lt. Col. Robert C. Buchanan and told him they did not wish to fight, but neither did they wish to be moved away from their homeland. Unfortunately, this meeting could not blunt the momentum toward forced removal of Native Americans to faraway “reservations”.

When the last battle on the Rogue River ended in defeat for the Native Americans, on May 27, 1956 at Big Bend, the survivors were marched downriver and then north along the coast to Port Orford. In June and July, hundreds (from numerous tribes in the area) were loaded on the ocean steamer Columbia, transported to Portland, and marched overland to the new reservations at Siletz and Grand Ronde, near the coast west of Salem. Soon after, Tecumtum and others, including Aggie’s great-grandparents, grandfather and great-aunts, were marched 125 miles up the Pacific Coast on a “Trail of Tears” to Siletz, suffering from harsh storms and inadequate supplies.

Eighty percent of the original estimated 9,500 Native Americans in southwest Oregon didn’t make it to the new reservations.

Great Aunt Agnes Harney Howard (Grandma Aggie’s namesake) made the long walk north, and her name was given to the little town of Agness, where the Illinois River flows into the Rogue. She married Joe Howard (Alsea/English), and lived with Aggie’s family at the Siletz Reservation in her later years.

Great Aunt Frances Harney Johnson also made the long walk up the coast and resettled at Siletz. Her Native name was “Quis-quas-hum,” and she was known to be full of fun. Frances met a young Army lieutenant, Phil Sheridan, who worked on Native American treaties and invited her and her brother, George Harney, to visit Washington D.C. Details of this trip are unclear, except for the 1874 photo of George by the Smithsonian Institute (below).

Great Aunt Frances bore the traditional 111 chin tattoos (that Grandma Aggie adopted after making friends with traditional tattooists from New Zealand). Frances was well-known among linguists as the source for Edward Sapir’s classic, Takelma Texts, published by the Smithsonian in 1926. Now out-of-print, this volume contains vocabulary and translations of Takelma stories, including one featuring the cultural hero “Dal-Dal,” or Dragonfly.

In the 1930s, Frances began to work with the famous linguist and anthropologist, John Harrington, providing personal accounts about her early life in the Takelma homelands in the Rogue Valley, before her forced removal to Siletz in 1856. Grandma Aggie remembers him well from his stays in their house.

In 1933, Frances (in her 90s) guided Harrington and his research party (including Grandma Aggie’s father and two brothers) to the Rogue Valley near Table Rocks. She led them to the Takelma village site at Ti’lomikh Falls upstream of Gold Hill, where she and Native Americans from numerous tribes had once celebrated the annual Salmon Ceremony.

In 2007, a long-lost 1933 picture of Aggie’s father, sitting in the Story Chair next to the falls, helped Grandma Aggie, Tom Doty and Steve Kiesling find this legendary Story Chair again and confirm the location of the Ti’lomikh Falls Salmon Ceremony site, a sacred place indeed. [for more see Rediscovering Ti’lomkh Falls]

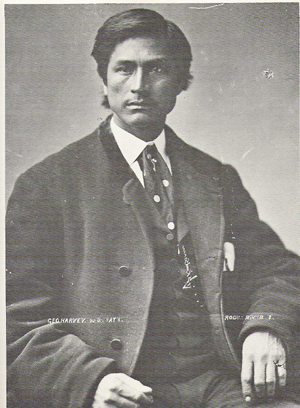

Chief George Harney

He was 19 years old in 1856, when he walked the 125-mile Trail of Tears from Port Orford to Siletz with what remained of his family. For the next 14 years he worked hard alongside people from 27 other tribes to adjust to the difficult new life on the reservation at Siletz.

By 1870, he had earned the respect of enough people to be elected the first chief of the approximately 2,000 residents of the Siletz Reservation.

He recognized the need to adapt to the ways of the settlers and was the first to own cattle. But he repeatedly stood up for the rights of his people and resisted efforts to abolish the reservation and relocate his people again. In 1873 he declared, “We were driven here, and now this is our home, and we want to stay.”

In 1876 Chief George criticized the new Indian Agent, William Bagley, because he “never seemed interested in our struggles to become tillers of the soil.” In 1877 he warned that the Alsea people, who had been forced to leave the reservation, were “dying off fast, from starvation.” In 1878, as chief of the Rogue River Indians, he signed a petition against Bagley along with 81 others, including chiefs of the Nestuccas, Tututnis, Sixes, Galice Creeks, Shasta Costas, Coquilles, and Joshuas.

In 1886, at 49 years, George Harney married Elizabeth Juliana Tole, Aggie’s Grandmother. She came from a well-to-do Chinook/Alsea/Lower Tillamook/Yaquina family in the Grand Ronde area. They had six children, one of whom was Aggie’s mother, Eveline Lydia. In the 1880s, George and his family converted to Catholicism. He is honored with his name in a stained glass window in the Siletz church of St. Mary’s, which he helped to establish.

George Harney continued to serve his people as chief until his death in 1900, at the age of 63.

Grandpa George Harney & Father George Wentworth Baker

In 1912 Aggie’s mother, Eveline Lydia Harney Baker (1888-1941), married George Wentworth Baker (1889-1944). George was the adopted child of Charles Wentworth Baker (Coos) and Mary Tipton (European). George worked in logging, making nets for salmon and steelhead fishing, and building boats. Eveline and George had nine children, and Aggie was the seventh. Both were known as a traditional healers.

Sources:

- Agnes Baker Pilgrim, personal communications, 11/05-2/06

- Steven Dow Beckham, Requiem for a People: the Rogue Indians and the Frontiersmen, University of Oklahoma Press, 1971, 214 pp.

- E.A. Schwartz, The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1980, University of Oklahoma Press, 1997, 354 pp.

- Lionel Youst, She’s Tricky Like Coyote: Annie Peterson, an Oregon Coast Indian Woman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1997, 307 pp.

- Stephen Dow Beckham, Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries, Oregon State University Press (Corvallis), 2006.